- http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2014/05/dogs_of_war_sergeant_stubby_the_u_s_army_s_original_and_still_most_highly.html

- http://amhistory.si.edu/militaryhistory/collection/object.asp?ID=15

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sgt_Stubby%27s_brick_at_Liberty_Memorial.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergeant_Stubby

Written by Jenifer Chrisman on April 10, 2018.

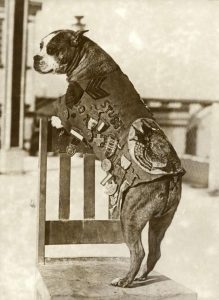

Original caption: Washington, DC: Meet up with Stubby, a 9-year-old veteran of the canine species. He has been through the World War as mascot for the 102nd Infantry, 26th Division. Stubby visited the White House to call on President Coolidge. November 1924

Eerste Wereldoorlog, Verenigde Staten. De Amerikaanse legerhond Stubby die de rang van sergeant had, overleed in 1926.

Stemming from a rich tradition dating back centuries, military trained dogs and their training schools were in place among many of the countries that became involved in World War I prior to the conflict. The United States was not among them.

Pedigreed dogs, such as Jack Russell terriers (rat chasers), Siberian huskies (transport), Airedale terriers (messengers), and German shepherds, Alsatian sheep dogs and Chienes de Brie (sentry duty), were favored. The Red Cross also used dogs to aid wounded and dying men by negotiating the battlefields with medical supplies and water or simply offering comfort.

In July of 1917, the soon to be named “Stubby,” and founding canine of the Army, wandered onto the field of Camp Yale (Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut) where the 102nd Infantry, 26th “Yankee” Division, were doing exercises in preparation for deployment. Stubby lingered near the field after his first appearance, eventually becoming the fastest of friends with a 25-year-old private, J. Robert Conroy.

Born in either 1916 or 1917, Sergeant Stubby’s provenance is unknown. Brindle patterned, he was considered a dog of “unknown breed,” a Bull (or Boston) Terrier mutt.

In September of 1917, Conroy was faced with a dilemma. Dogs were forbidden by the military, but the 102nd was preparing to ship out after their three-month training and he didn’t want to leave Stubby behind. After traveling to Newport News, Virginia, via rail, the 102nd boarded the freighter SS Minnesota, Stubby concealed in Conroy’s Army-issue greatcoat. Conroy then hid Stubby in the ship’s coal bin down in the hold.

Stubby became the 102nd's unofficial mascot after he was discovered during the crossing. He was popular with the crew of the SS Minnesota and one of the onboard machinists fashioned a set of metal “dog tags” for him.

Despite not serving in an official capacity after their landing in France, Colonel John Henry Parker, the regiment leader gave special orders for Stubby to remain. Stubby was even issued a gas mask (which likely saved his life on Saint Patrick’s Day of 1918), although it didn’t fit his physiognomy well. The 26th took part in 17 engagements and four major offensives over a total of 210 days.

At Chemin des Dames, where his own life was saved by his mask, Stubby was the first to smell the gas from the early morning assault. Running up and down the trenches, Stubby bit at and barked at the soldiers in order to get them to safety. Stubby achieved his first military rank, private first class, on April 5, 2018.

After recovering from a war wound north of Mandres-aux-Quatre-Tours at a place knows as “Dead Man’s Curve,” in July of 1918 Stubby savagely attacked a soldier at Chateâu Thierry. He had learned to distinguish between the German gray serge and U.S.’s khaki doughboy uniform. He had to remain tied up whenever prisoners were being brought in. But Stubby’s newfound knowledge served him well when he sniffed out a German soldier hiding in nearby bushes in Argonne. He received The Iron Cross after giving chase and eventually dragging the soldier back to his unit.

After the war ended on November 11, 1918, Stubby was waiting for the trip home from a protracted demobilization when he met President Woodrow Wilson in Mandres en Bassigny on Christmas day.

Stubby and Conroy demobilized at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, on April 29, 1919. He met with President Warren G. Harding at the White House in 1921, and Harding’s successor, President Calvin Coolidge, on three separate occasions. Stubby also became the official mascot at Georgetown when Conroy attended law school.

Doors were opened to Stubby that were usually closed to dogs. He became a member of the American Legion and the Red Cross, was allowed to stay the night at Hotel Majestic on Central Park and was granted a lifetime membership to the YMCA, which entitled him to “three bones a day and a place to sleep” for as long as he lived. Conroy also kept a comprehensive scrapbook which is housed at the National Museum of American History - Smithsonian Institution.

Although many of the clippings within the scrapbook conflict, there is no doubt Stubby served in France during World War I. And his celebrity at home helped to heal a country that, for the first time, saw carnage on such an unprecedented scale. Even so, not everyone was enamored with him.

Robert Conroy remained in government service after the war, first at the Justice Department with the Bureau of Investigation (FBI predecessor), then with military intelligence and finally as secretary for a Connecticut congressman on Capitol Hill. Stubby remained with Conroy until his death on March 16, 1926. He died in Conroy’s arms. Stubby’s taxidermied remains, along with the carrier pigeon Cher Ami and a doughboy mannequin, are on view at the Smithsonian.

Sources: